Belief

Definitions

Belief is the (psychological) state of holding a proposition to be true.

You can hold beliefs independent of the existence or validity of evidence or justifications for the belief, and regardless of whether what is being believed is probable or improbable.

Readings

The usual starting points:

- Wikipedia: Belief, Certainty, Skepticism.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Belief, Certainty, Skepticism.

Belief vs. Knowledge

How is belief different from knowledge? For one thing we can believe things regardless of whether they are true. You might believe something because:

- You have been conditioned to believe it since an early age.

- An authority figure told you it is true.

- It sounds really cool.

- It jives with your political persuasions.

- It corresponds with evidence — one piece of evidence.

- It corresponds with evidence — many pieces of evidence.

- It has predictive power.

- No one has ever shown it false, despite valiant efforts to do so.

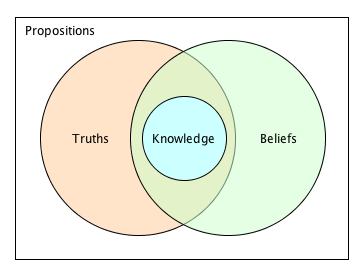

You can believe things that are true or false. A subset of true beliefs are what you know. You might believe something to be true, and it might be true, but not know it. Make sense? Here's the classic picture:

To Plato, knowledge was justified true belief.

Belief Logics

Usually we use the term doxastic logic to refer to the logic of beliefs, and epistemic logic to refer to the logic of knowledge, but some people use the term "epistemic" for both. In doxastic logic:

| $\mathcal{B}_x A$ | means agent x believes A |

| $\mathcal{B}A$ | means the assumed agent believes A |

Here are some classic statements. Let g be the proposition "gods exist" (or "God exists" if you prefer). Let the agent be assumed. Then:

| $\neg \mathcal{B}g$ | means the agent does not believe that gods exist |

| $\mathcal{B}\neg g$ | means the agent believes that gods do not exist. |

The difference between the above to statements is made very clear in the logic, even though it gets blurry (to some) when just reading the English.

Here's another one. Let $G$ be the predicate “is a god,” $E$ be the predicate “exists,” and $y$ be some particular entity. Then:

| $\forall g. (Gg \supset (g = y \supset \mathcal{B}(Eg)) ∧ (g ≠ y \supset \mathcal{B}(\neg Eg)))$ |

means the agent believes that god $y$ exists but that no other gods exist.

Here are some statements involving different kinds of reasoners (from Smullyan):

| $\forall p. \mathcal{B}p \supset p$ | Accurate |

| $\exists p. (\neg p \land \mathcal{B}p)$ | Inaccurate |

| $\mathcal{B}(\neg \exists p. (\neg p \land \mathcal{B}p))$ | Conceited |

| $\neg \exists p. (\mathcal{B}p \land \mathcal{B}\neg p)$ | Consistent |

| $\forall p. (\mathcal{B}p \supset \mathcal{B}\mathcal{B}p)$ | Normal |

| $\exists p. (\mathcal{B}p \land \mathcal{B}(\neg \mathcal{B}p))$ | Peculiar |

| $\forall p. \forall q. (\mathcal{B}(p \supset q) \supset (\mathcal{B}p \supset \mathcal{B}q))$ | Regular |

| $\exists p. (\mathcal{B}\mathcal{B}p \land \mathcal{B}p)$ | Unstable |

| $\forall p. (\mathcal{B}\mathcal{B}p \supset \mathcal{B}p)$ | Stable |

| $\forall p. (\mathcal{B}(\mathcal{B}P \supset p) \supset \mathcal{B}p)$ | Modest |

Undecidability of Doxastic Logic: You cannot be an accurate reasoner and assign a truth value to all propositions. How would an accurate reasoner assign a truth value to:

“I will never believe this statement.”

As with arithmetic, an accurate reasoner cannot be both consistent and complete.

Belief and Delusion

While there are many academic treatises on belief and delusion, it's fun to watch some TED talks every now and then. Michael Shermer has done a couple. His first was on why people believe stupid things:

He has a second talk, not as good (it has a couple of dumb examples and a useless Candid Camera clip at the end), but it had a couple interesting quotes (e.g., "Belief is the natural state of things. It is the default option.") and a useful distinction between Type I and Type II errors. Rather than watching Shermer's second video you can read his book The Believing Brain or watch this short video with some ideas from the book:

Belief without evidence (heh, even "evidence" can be a messy term — one person may view X as evidence for Y while another person views X has having nothing whatsoever to do with Y) is very common.

Occasionally pollsters look into what people believe. The oft-cited Harris Poll of 2,250 American Adults in 2013 on What People Do and Do Not Believe in found:

- 74% believe in God

- 72% believe in miracles

- 68% believe in heaven

- 68% believe Jesus is God or the son of God or both

- 68% believe in angels

- 65% believe in the resurrection of Jesus

- 64% believe in the survival of the soul after death

- 58% believe in hell

- 58% believe in the devil

- 57% believe in the virgin birth of Jesus

- 47% believe in evolution by natural selection

- 42% believe in ghosts

- 36% believe in creationism

- 36% believe in UFOs

- 29% believe in astrology

- 26% believe in witches

- 24% believe in reincarnation

Check out the article on delusion at the SEP.

Illusion

We know our brains evolved to sense things that aren't there or aren't what we think there are. We (1) are pattern seekers, and (2) we evolved certain capabilities, like recognizing faces. Illusionists exploit this fact. Lots of links:

Justification

How are beliefs justified?

Read about Justification Logic in the SEP. Justifications make epistemic or doxastic logic multimodal; we get terms like:

r:A

meaning "proposition (or formula) A is justified by reason r."

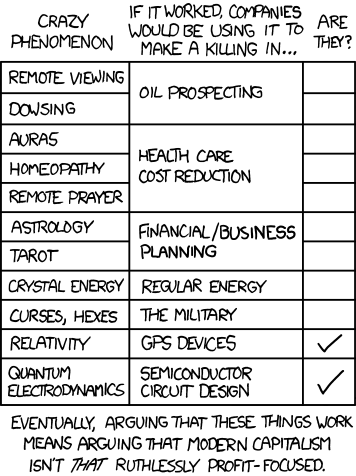

Randall Munroe suggests the Economic Argument in xkcd 808:

Belief Revision

Sometimes things seem so right but they turn out to be right only at some level. When "scaled up" they are wrong. Here's a great minute physics video that illustrates a couple of these cases:

And another one showing that, yes, the effects of relativity really do matter for GPS:

Reasoning with Uncertainty

Much of the study of logic deals with how we move from premises to conclusions, where the form of the argument matters most. We often don't care about the truth of the premises; we just like to know whether the conclusion follows from the premises.

But how might our degree of certainty in the truth of the premises — our degree of belief in the premises — affect our reasoning? There are several approaches to this question. One is subjective logic.

Read about subjective logic at at Wikpedia.