Philosophy of Science

Overview

The philosophy of science deals with the practice, methods, workings, implications, and values of science. Philosophers of science are concerned with what distinguishes science from nonscience, and about topics such as reasoning, induction, realism, explanation, reductionism, empiricism, validation, and the "social impact" of science.

Read more at:

- Wikipedia's Philosophy of Science article

- SEP search result for "Philosophy of Science"

- Philosophy of Science at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science: A Very Short Introduction (Book)

What is Science?

You'll get lots of definitions if you look up this word in a dictionary (dicitionary.com, Merriam-Webster) but Wikipedia's got a good one:

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

You probably already heard about how "modern day" science can trace back to Mikołaj Kopernik, and how others such as Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton contributed their ideas and methods and we now have this system that values:

- Careful observation

- Hypotheses of broad principles that explain the observations

- Hypotheses that make testable predictions

- A preference for simplicity when formulating general theories

- Experimentation

- Analysis

- Falsification

- Peer Review

- Repeated verification

- Finding errors in others' work

- Skepticism, even of "authority"

Philosophers of science look at these aspects, and more.

History of Science

In addition to the scientific method and the body of knowledge we now have in scientific fields, it's helpful to have a sense of the history of discoveries in science, people's immediate reaction to them, how they became accepted, how they were applied, and sometimes, how they were extended or even supplanted.

Often knowledge evolves through better measurement. Sometimes there are true scientific “revolutions,” for example:

- Copernican Revolution: Heliocentrism

- Newton: Principia (Tyson on Newton)

- Einstein et al.: Relativity, Quantum Mechanics

- Darwin: Natural Selection

- DNA, Molecular Biology, Genetics, Genetic Engineering

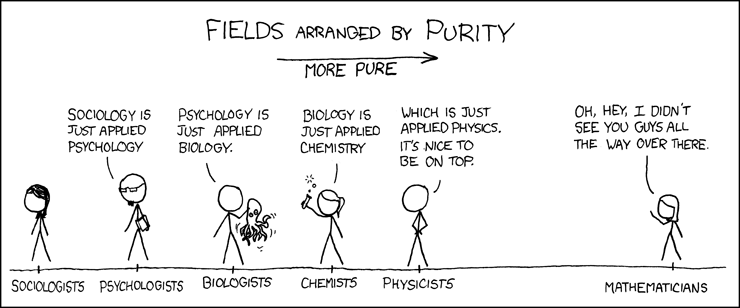

Why does physics keep popping up here?

Philosophers of science pay great attention to the historical aspects of scientific discovery and application.

Demarcation

Science differs from pseudo-science, junk science, voodoo science, bad science, pathological science, nonscience and just plain nonsense, to paraphrase Michael Shermer. But how?

Is there a clear line of demarcation between science and nonscience, or is science perhaps just a set of activities that loosely share some main features?

There have been claims in the past about what constitutes a demarcation:

- "Well-reasoned" arguments

- Empiricism

- Falsifiabilty

- Puzzle-solving

But all of these have problems.

Some have even said the whole demarcation problem is without merit.

Some philosophers of science are interested in this; many are not.

Reasoning

Philosophers of Science are interested in the nature of scientific reasoning. What kinds of reasoning do we know about?

- Deduction The premises necessarily entail the conclusion.

- Induction (Nearly) Every x up to this point has been y, so the next x will also be y.

- Abduction x happened, and y is the best explanation for x, so y must have happened.

Abduction explicitly appeals to explanatory or causal effects; induction appeals only to quantitative effects.

Read about these at Wikipedia and the SEP.

Induction

Induction and abduction (a.k.a inference to the best explanation) are not precise, and may lead to false conclusions. But we have to use them, right?

Hume's Problem of induction: Induction can only be justified... inductively! Wow, good stuff. Possible solutions:

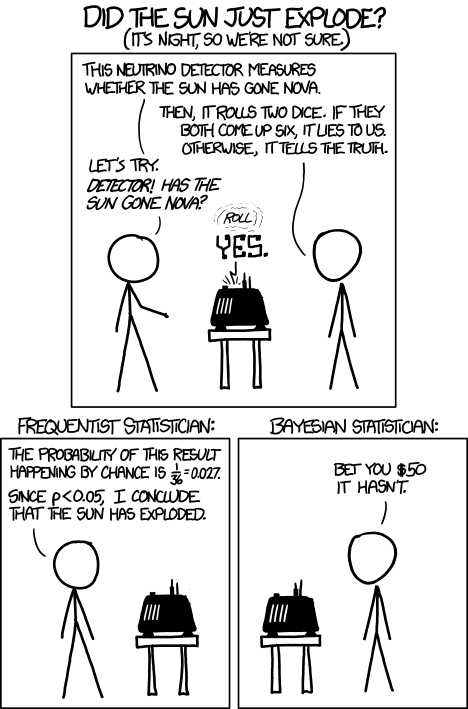

- It's the probability, stupid.

- So what. Treat induction as fundamental, like hardware.

But probability doesn't solve the problem, regardless of the interpretation: frequency, subjective, or logical. The frequency interpretation ultimately relies on induction! Ouch! Subjective probability doesn't even begin to address the problem (it's all about hunches). So that leaves the logical interpretation which....

Finally, speaking of probability:

Abduction

What might a philosopher of science wonder about abduction? A couple things, at least:

- Which is more foundational: abduction or induction? Or neither?

- What are the criteria for the best explanation? Conciseness, simplicity, parsimony?

Ockham's Razor

Why should we generally make only the simplest assumptions (or assume the simplest causes)? Because we can keep on adding further assumed "causes" until — voila — the theory is explained.

Ockham's Razor is the principle that one should make no more assumptions than necessary.

It is a heuristic not a law. And it is often misued! The RationalWiki article advises: "It's probably best to avoid ever citing Occam's razor unless you're damn well sure you know what you're doing with it."

Coherence and Foundationalism

If a scientist makes a claim C then there should be a justification C1. But that's a claim, too, so we need to justify it with C2. Another claim? When does it end?

We can regress down to a basic claim, something we take as inherently true, not in need of any justification. This is foundationalism.

Or we regress down to a claim which is part of a coherent set of claims. This is coherentism.

Explanation

What makes an explanation "scientific"?

Hempel's Covering Law

Hempel offered the following as a structure for scientific explanations:

General Law Specific Facts ----------------------------------- ∴ Phenomenon to be explained

Sometimes it seems to work, as in this example from Okasha:

Laws of trigonometry The sun is 37° over the horizon The flagpole is 15 feet high -------------------------------------------- ∴ The flagpole shadow is 20 feet long

But there are at least two obvious problems with the covering law, as in these two examples from Okasha:

- Symmetry: It also "explains" why the flagpole is 15 feet high given the length of the shadow.

- Irrelevance: It "explains" why men taking birth control pills don't get pregnant.

Causality

Can we fix the covering law by requiring relevance, and ... causality? It's plausible but not everyone would accept this.

- Empiricists are suspicious of causality because causality can not be "experienced."

- What is causality?

To see how large of a topic causality is in philosophy, try this Google search.

What can science not explain?

If you are going to claim something can not be explained, you should have a good reason for saying so, not just "well we don't know yet." But there are a few serious directions people have taken:

- Some things are just really mysterious and at least to some defy explanation. For example,

there's the Hard problem

of consciousness.

Exercise: Contrast the views of (1) Dennett and (2) McGill on this issue.

- Chains of explanations keep on going, so maybe some things are just too fundamental?

- Why do electrons behave the way they do?

- Where did the electrons come from? And if we ever explain that, then how to explain that clause?

- Why is there gravity? How did it get separated from the other forces?

Exercise: Got more of these? - There's the problem of multiple realizations. It's hard to say biology is precisely reducible to physics

because the abstraction of the "cell" isn't exactly describable in physics. What exactly is and isn't a cell

in terms of molecular arrangements? What is and is not pain? An economy?

Exercise: Read the multiple realizability article at the SEP. How have reductionists challenged this doctrine?Exercise: Read Dawkins's essay The Tyranny of the Discontinuous Mind, in which he discusses the continuum of intermediates. How is this related to multiple realizability?

Realism

The ancient philosophical debate between realism (nature exists independent of conscious observers) and idealism (no it doesn't) isn't part of the philosophy of science, but the debate between scientific realism and instrumentalism is.

Scientific Realism and Anti-Realism

Traditionally realism refers to the idea that the universe has a true existence outside of the perception of conscious beings. It's opposite is idealism. But when it comes to science we have a related distinction:

| Scientific Realism | Anti-Realism |

|---|---|

| Science aims to provide a true description of the universe. | Science aims to describe only the observable part of the universe. |

| Quarks, leptons, bosons, and hadrons really exist. | Unobservable things like quarks, leptons, bosons, and hadrons are only convenient fictions that help describe things and make predictions . |

| Science can help us discover reality. | The unobservable is beyond our knowledge; we are limited by our senses. |

| Why is the atomic theory so successful (e.g., lasers work as predicted based on the energy state transitions of electrons), were it not actually real? We don't want to believe in miracles. | Not so fast! Phlogiston turned out to not be real. The "ether" turned out not to be real. So did lots of other empirically successful things. Maybe there is another non-miraculous explanation for lasers. We just don't know. |

| What's wrong with tools to enhance one's powers of observation? Are binoculars, telescopes, microscopes, electron microscopes, particle detectors not appropriate? Why would you object to these? | Okay so the dividing line between observable and unobservable is fuzzy, but we still have clear-cut cases. |

| Underdetermination is not a problem: this argument rules out the reality of unobserved entities as well as unobservable. It's just a complaint about induction. | Underdetermination is a serious philosphical problem. The claims science makes about the unobservable are justified by only by observable behavior. Therefore, there will always be alternative explanations. |

| Even though multiple explanations may exist regarding the unobservable, there's often a best explanation (e.g., the simplest), and sometimes it's hard even to find one. | Best and simple don't mean true. |

Scientific Progress

Philosophers of science are interested in how sciences changes, or progresses. When does it just slowly evolve? What constitues a scientific revolution? Are there patterns in the way ideas change?

From Logical Positivism to Kuhn

The Logical Positivists (Wikipedia, SEP)

- Hated metaphysics

- Stressed verificationism

- Distinguished the context of discovery from the context of justification

- Felt the former was subjective and probably didn't even matter, while the latter was objective and rational

- Asserted that rival scientific theories could in principle be analyzed and a "winner" determined

- Was declared by Passmore to be "as dead as a philosophical movement ever becomes"

Thomas Kuhn's 1963 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was hugely influential. He said

- The history of science matters

- Scientific revolutions happen infrequently but are characterized by paradigm shifts (the existing outlook, beliefs, assumptions, world-view, values, etc. all change)

- "Normal science" was what was done between the paradigm shifts

- Normal science involves fine-tuning the current paradigm to support any anomolies that pop up

Okay, cool so far. Not very controversial. Even though the Darwinian and Einsteinian revolutions fit Kuhn's model, but the molecular biology one doesn't, the ideas are plausible. But Kuhn made some claims that did generate controversy....

Adoption of New Paradigms and Theory Dependence

Kuhn also claimed:

- New paradigms are adopted not necessarily on the basis of new objective evidence, but possibly on peer pressure—the new paradigm may simply have more forceful advocates

- Objective truth is questionable. Facts are paradigm-relative. How did he justify this?

- Competing paradigms are "incommensurate." You can't always translate one concept in one paradigm into one concept in another: concepts cannot even be explained independently of a paradigm. (Example: "mass" to Newton vs. Einstein.)

Rationality

Do Kuhn's claims (if valid) show science to be a rather non-rational endeavor? He didn't exactly mean that...

- He said he was trying to give a more accurate picture of how science progresses; in other words, there was no algorithm for selecting the best theory.

- Rationality is not defined by there being an algorithm; you can still be "rational" by making informed choices.

Social Aspects of Scientific Progress

After Kuhn, we now consider

- science to be a social activity: paradigms are collectively understood, people play by rules...

- the history of science should not be ignored; discovery and justification are both important

But some have misinterpreted Kuhn, or taken his ideas in radical directions, sometimes by:

- claiming science itself is relative to the culture in which it is practiced

- rejecting objective truth outright

- claiming truth is relative to culture (cultural relativism)

Problems in Specific Disciplines

Absolute Space

Newton's concept of space was absolutist: space always existed and has a fixed 3-D coordinate system; at some point perhaps matter was placed into this absolute space. Leibniz's was relational: space is defined by the relations between what it contains, and did not exist before the creation of all things.

- Why believe Leibniz? (1) Identity of Indiscernibles. (2) Motion can only be detected relative to other things, not to absolute space, so the idea doesn't make sense.

- Why believe Newton? (1) Absolute space must exist because it's the only thing left when certain thought experiments remove objects that another object supposedly moves relative to. (2) Absolute space detectable as the only thing that certain acceleration can be relative to.

This question is still being debated.

Philosophy of Biology

See Wikipedia for this.

Biological Classification

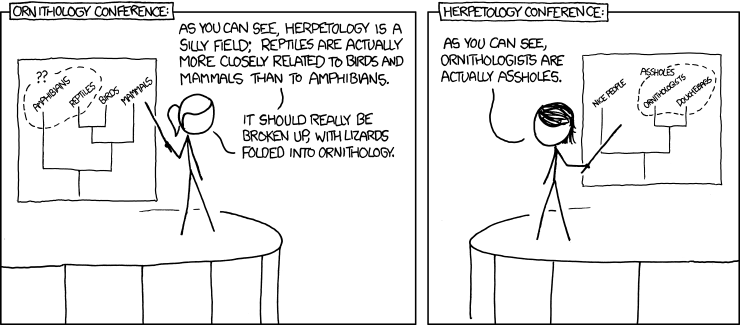

How should we choose to classify organisms? Two opposing schools of thought:

- By similarity of features and behavior (Pheneticism)

- By evolutionary ancestry ONLY (Cladism)

See the difference? Let Randall Munroe explain it:

So cladists are really into the phylogenetic relationships. See the Wikipedia article on the phylogenetic tree for more information, and some lovely diagrams.

Speaking of diagram, please take the time to study this beautiful tree of life diagram, because it shows more than just today's species; it gives you a good sense of the history of life on Earth (including those pesky mass extinctions!)

Why does this debate matter?

- Pheneticism is hard to justify as exact science because sometimes classification boundaries are "value judgements."

- Pure cladism is..., well..., how do you really know you got it right?

Modularity of the Mind

Is the mind a general-purpose problem solver, or is it made up of specialized modules that are (to some degree) independent of each other? Or a bit of both?

Fodor noted some properties of cognitive modules, including:

- Domain Specificity: the module is useful only for one task but not others.

- Mandatory: the module cannot be turned on and off.

- Information Encapsulation: the module cannot access certain information it could use (optical illusions remain after the secret is given away, harmless snakes are still scary to some people...)

Brain injuries, language learning, and some experimental data strongly support modularity, but is the whole brain modular? How does a juror go about determining a defendant's guilt or innocence? What module is that? What module recognizes a second cousin?

But how is any of this of concern to philosophy? Some ideas:

- We'd like to know which parts of the mind are modular (perception? language?) and which are not (thinking? reasoning?)

- Perhaps modular systems are easier to study scientifically?

- How would we go about coming up with a scientific understanding of non-modular systems?

Ideology and Morality

Because the philosophy of science is concerned with social aspects of science, we sometimes see science and ideology and (perhaps ethics getting mixed up together). Samir Okasha writes "advocates of sociobiology have tended to be politically right-wing, while its critics have tended to come from the political left."

Wait, what? Left and right? What do those terms mean? Jonathan Haidt has a pretty good answer:

Interesting, eh? Haidt is introducing 5 dimensions of morality: harm avoidance, fairness, in-group loyalty, authority, and purity. (For more, see Haidt's essay in Edge.) Now the next question is, can science explain morality? Sam Harris says it can:

Criticisms

Science is effective for many reasons: it is a "collective pursuit," it tends to root out mistakes over time, etc. Are there any criticisms? The philosophy of science looks at criticisms, too.

- Works better in theory than in practice. People are motivated to get grants. People often don't like admitting mistakes.

- Science worship. Some hold to an elitist attitude that scientists are all that, and that nonscience disciplines (e.g. philosophy) are inferior. (But is this really a criticism of science itself?)

- Scientific imperialism. Some hold that all questions are scientific questions and that all knowledge can be generated by scientific means. Others reject this idea, even though they admit no mysticism and transcendentalism whatsoever.

- One size fits all. Should the social sciences adopt the same methods as the natural sciences? Are societies or human nature more complex that physical nature or are they the same?

- Science leads to negative as well as positive technologies. Yes there are nuclear

bombs and polluted rivers. But....

Exercise: But what?

- Money spent on science should be spent on immediate social needs. You'll get heated arguments on this one. To many, science is woefully underfunded and in fact contributes far more to society's well being in the long run. (See Penny4Nasa and any of several video appearances or articles by NdT on the NASA Effect.)

- Science is seen by some as "hostile to religion." One argument goes something like

this (although there are many other dimensions):

- Natural science describes a universe incompatible with a literal reading of allegorical creation stories.

- Creation stories belong to many religions.

- Therefore, scientists hate religion.

Exercise: What do you think of that argument? Does anyone really hold it?Exercise: Can modern science disprove Turtles all the way down?Exercise: Many if not most members of religions take their creation stories as allegorical, yet some scientists and thinkers (e.g., Dawkins, Hitchens) are openly hostile to religion, period. What are their arguments? What are the counter-arguments to these arguments? - Science can't possibly be value-free. Because scientists get a chance to choose their research programs and are sometimes funded by agencies with practical purposes, there really is no research for its own sake.

Case Study

Chris Mooney has written a book called The Republican War on Science, about the "conservative agenda to put politics ahead of scientific truth." Fine. But the left can attack "scientific truth" too. How?

Start by watching this video, by Steven Pinker. He cites real numbers!

Pinker even has a book on this topic too. Note the claims made about rates of violence (or at least the chance of dying a violent death at the hands of another person) being higher in certain societies than others.

Now, check out this article. Note the interesting tagline: "Respected author's book condemned by Survival International as 'completely wrong, both factually and morally'."