Internet Basics

Unit Goals

The Beginning

The Internet grew out of the old ARPANET. The ARPANET was created to (1) allow the government to give research institutions only one computer each and let them share computing power, and (2) withstand nuclear missile attacks. The ARPANET was pretty revolutionary; it practically introduced:

- Packet Switching

- Distributed Routing

- Multiple Links

- Internetworking (IMPs)

In 1969, there were only four hosts:

In the early days, the ARPANET had competitors, such as BITNET, ALOHANET, FIDONET. Little by little, most everything merged into today’s Internet.

Overviews and Histories

If time permits, read these; they are really good:

- Hobbes' Internet Timeline

- Wikipedia's Internet article

- The Living Internet

- A very old but still relevant quick course on the Internet

- The History of the URL

Here are some events I like:

- 1961: Kleinrock’s paper on packet switching

- 1969: ARPANET begins!

- 1971: ARPANET at 15 nodes

- 1972: First email sent

- 1973: ARPANET gets European connections

- 1974: Cerf and Kahn paper

- 1976: Ethernet created at PARC

- 1978: TCP split into TCP and IP

- 1979: ARPANET has 200 nodes

- 1983: TCP/IP now required

- 1984: DNS

- 1984: ARPANET has 1000 nodes

- 1985: FTP

- 1987: 10000 hosts

- 1988: IRC

- 1988: FidoNet rolled in

- 1990: HTTP and HTML

- 1991: WAIS and Gopher and WWW and PGP (all in the same year)

- 1992: One million hosts

- 1993: Mosaic

- 1995: Java and JavaScript

- 1996: Backrub

- Late 1990s: Gigabit backbone, tens of millions of hosts, Instant Messaging

- 2000: New TLDs

- 2004: Slammer worm

- 2000s: Hundreds of millions of hosts, broadband in homes, phones as computers

- 2008: IPv6 added to root zone servers

- 2011: Non-Latin TLDs

- 2013: Billion hosts

- 2014: Heartbleed and Shellshock

- 2017: WannaCry

- 2017: AIM shut down

Here’s a brief video on how it all began:

This one’s even shorter:

Impact

Note how networking and our use of networks becomes qualitatively different as devices get faster and the Internet backbone, pipes, core, routers, switches push more and more data through at much faster rates than before:

- In addition to text, images, and animated gifs, we now stream HD video, much of which is produced live.

- Audio is no longer just beeps or voice or sound effects but is now HD.

- Trading of commodities is now at the millisecond time frame or less.

- Voice and multimedia content no longer needs analog transmission lines; IP is great.

- Real-time navigation and teleconferencing is for everyone now

- Sensors are everywhere, spying on everyone: your data and identity is at risk.

- Entertainment is now pretty much on demand.

- Social networks give instant access to the news, which can be distorted. Everyone has a soapbox.

Areas of Study

The three main areas of study regarding internets are:

| Area | Topics |

|---|---|

| Architecture | How the Internet is connected, how the hosts and networks are numbered. The ideas behind packet switching. |

| Protocols | What hosts and other devices say to each other. |

| Services | Those things end users find useful. |

Internet Architecture

The networks on the Internet are pretty much hierarchically organized. Data from your personal device data may travel:

- from your device

- through its network card

- possibly to the LAN in your building and then to a firewall

- to a modem (necessary for long distance communication)

- to the Local Loops carrier (cable, phone lines, power, satellite, wireless media, ...)

- to an ISP

- to the backbone (really high capacity routers connected together with really great physical transmission media)

- Then back down the levels to the destination computer

The Edge

The edge (of the Internet) contains the devices (phones, tables, laptops, desktops, printers, scanners, speakers, IoT things) and the routers or cell towers to which they directly connect. Within a home or business network, you have LANs (Local area networks), based on WiFi (~50 Mbps) and Ethernet (~100 Mbps and even up to ~10 Gbps). These LANs often connect to an ISP via Cable, DSL, or Satellite.

- DSL has dedicated lines to the central office (~1 Mbps up, ~10 Mbps down). Uses phone lines, but voice and data are on different frequencies.

- Cable shares its lines among other homes in the neighborhood to the provider (~3 Mbps up, ~40 Mbps down). Uses cable, but TV and data are on different frequencies.

There are also WANs (Wide Area Networks) for your cellphones and cars. Range is several tens of kilometers. Speed varies.

The Core

The ISPs and their interconnections are called the core.

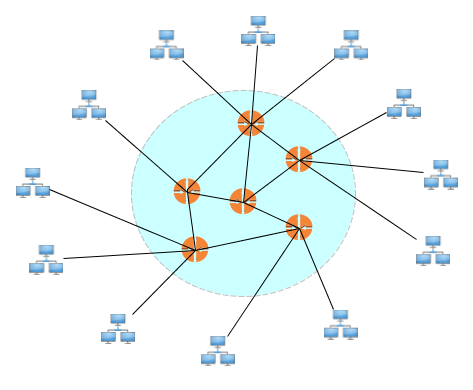

How does an internet core evolve? At first, the networks hook into a central, global, Internet Service Provider (a “global ISP”):

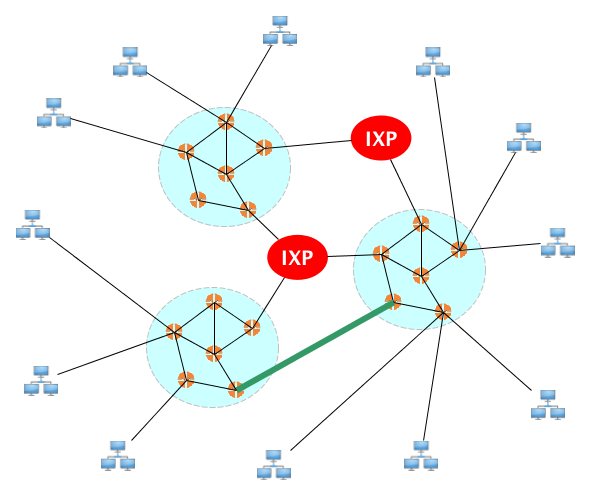

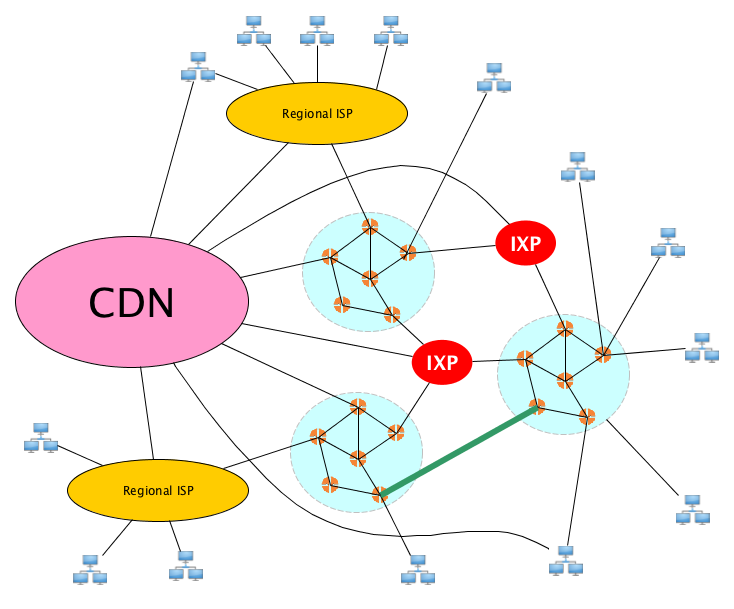

But that's becomes too big to handle, so new ISPs jump in, connected to each other via internet exchange points (IXPs) and peering links:

Then you get a hierarchy with regional ISPs, then big content providers create content delivery networks (CDNs) that sometimes may bypass the usual ISP architecture to get content close to end users.

Standards

The Internet is a world-wide network. It won’t work unless there are some standards everyone can agree upon.

The authoritative set of standard are the Internet RFCs. The describe and define technical aspects of the Internet, including low level and high level protocols, and other standards. RFC is an abbreviation for Request for Comments (RFCs). RFC 1 was written in 1969, and they are still being written today.

Here are some RFCs and their titles:

- RFC 768: User Datagram Protocol (UDP)

- RFC 791: Internet Protocol

- RFC 792: Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP)

- RFC 793: Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

- RFC 826: An Ethernet Address Resolution Protocol (ARP)

- RFC 959: File Transfer Protocol (FTP)

- RFC 977: Networks News Transfer Protocol (NNTP)

- RFC 1034: Domain Names: Concepts and Facilities

- RFC 1035: Domain Names: Implementation and Specification

- RFC 1112: Host extensions for IP multicasting

- RFC 1208: A Glossary of Networking Terms

- RFC 1541: Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP)

- RFC 1700: Assigned Numbers

- RFC 1723: Routing Information Protocol (RIP)

- RFC 1883: Internet Protocol, Version 6 (IPv6) Specification

- RFC 1918: Address Allocation for Private Networks

- RFC 1945: Hypertext Transfer Protocol -- HTTP/1.0

- RFC 2068: Hypertext Transfer Protocol -- HTTP/1.1

- RFC 2401: Security Architecture for the Internet Protocol

Protocols

A protocol defines the format of messages, how their content is to be interpreted and processed, and how they are to sent and received. The RFCs define ARP, IP, ICMP, IGMP, TCP, UDP, HTTP, FTP, TFTP, SMTP, POP, IMAP, HTTP, DNS, DHCP, VoIP, SIP, and dozens more.

On the global Internet, there are millions of applications, dozens (but still an unlimited number) of different kinds of individual networks (on the link layer), and a few different transport layer protocols (TCP and UDP are by far the most common).

But there is only one network layer protocol: IP. And that is, perhaps, what makes it awesome.

IP

IP is what makes the Internet the Internet. IP is:

- Unreliable: Packets might be dropped.

- Connectionless: Packets may be delivered out of order.

These properties make the protocol simple, lightweight, fast, and easy to implement. All the complex stuff like congestion control and resending and sequencing happens at the endpoints, not in the routers. And the simplicity also means it is really easy to implement over any link layer.

Note that the transport layer need not be reliable! TCP is, UDP is not. Why? Not every application needs to be perfectly reliable. Voice and video applications can drop packets and human users will probably still be okay with that.

It’s not trivially simple though, because that would be bad. So IP adds some features:

- Best effort: It promises to only drop packets if it has no choice (e.g. router buffer full).

- Loop avoidance: Packets have a TTL and are dropped when it reaches 0. (This means that if a packet is stuck in a routing loop, it will be dropped.)

- Checksumming: The header contains a checksum which should be verified, at least at the endpoint, to make sure nothing was corrupted

- Fragmentation: If a router knows that on the next hop, there is a network that can only handle packets of a size smaller than one it is looking at now, the router will fragment the packet into smaller ones (with information in each header to allow reassembly).

So the Internet was built with stateless routers, best effort delivery, no centralized control, no work to add networks to it—they just have to speak IP....

“The Internet was done so well that most people think of it as a natural resource like the Pacific Ocean, rather than something that was man-made. When was the last time a technology with a scale like that was so error-free? The Web, in comparison, is a joke. The Web was done by amateurs.” — Alan Kay

TCP

You might have heard the phrase “TCP/IP.” TCP and IP were actually designed together back in the 1970s. TCP is a transport layer protocol, built on top of IP. Where IP is connection-oriented and unreliable; TCP is connection-based and reliable. Its design provides a way to deliver packets reliably, in order, without loss or duplication, all on top of an unreliable network layer protocol.

Services

An internet service is used by end-users. Users can use them directly or go through a programming interface.

Categories of services include games, e-commerce, banking, social networking, email, and chat.

Specific services (or applications, even) are FTP, Telnet, WWW, VoIP, Gopher, News, Email. and many, many more.

Common Tools

Let’s get familiar with some tools and utilities for browsing, analyzing, and troubleshooting networks.

Command Line Utilities

The following are good to know:

| Command | Oversimplified Description | Information |

|---|---|---|

| ping | See if a host is up | Linux • macOS |

| ifconfig | Configure network interface parameters (Deprecated on Linux, use ip instead) | Linux • macOS |

| ip | Show and configure devices, routing, tunnels, and more | Linux |

| traceroute | Print the route that packets take to network host | Linux • macOS |

| dig | Get information about DNS | Linux • macOS |

| whois | Internet domain name and network number directory service | Linux |

| nslookup | Query Internet name servers interactively | Linux |

| netstat | Show network status | Linux |

| lsof | List open files | Linux • macOS |

| telnet | Communicate with another host using the insecure TELNET protocol. Convenient for debugging but don’t use it because it’s insecure. | Linux |

| ssh | Securely log in to a remote machine | Linux |

| scp | Securely copy files to/from a remote machine | Linux |

| nc | Do just about anything you can think of regarding TCP and UDP. Connect, listen, etc. | Linux • macOS |

| w | Display who is logged in and what they are doing | Linux • macOS |

| nmap | Open source tool for network exploration and security auditing | Linux |

| tcpdump | Dump traffic on a network | Linux • macOS |

There are so many more.

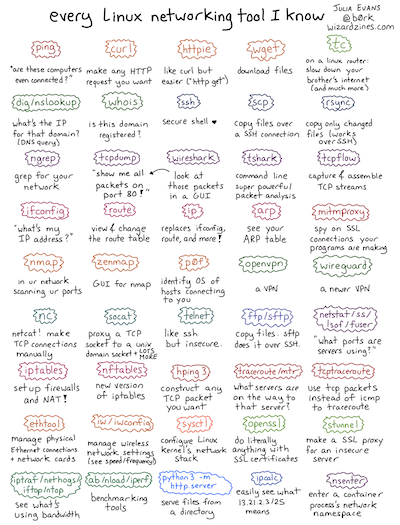

And you should check out this totally awesome poster by Julia Evans. Here’s a thumbnail of the poster to convince you that you need to check out the full-size poster:

Most of these will be covered during the course as needed, but we’ll look at the simpler ones below.

Do you prefer detailed technical references?

You might be interested in this index of man pages from Section 8 of a Debian Linux manual.

ping

Sends messages to a remote computer and receives an indication of whether it is alive.

From the man page: ping uses the ICMP protocol’s mandatory ECHO_REQUEST datagram to elicit an ICMP ECHO_RESPONSE from a host or gateway. ECHO_REQUEST datagrams (“pings”) have an IP and ICMP header, followed by a struct timeval and then an arbitrary number of “pad” bytes used to fill out the packet.

Here’s an example. I pinged www.google.com from an AWS EC2 box.

$ ping www.google.com PING www.google.com (172.217.15.100) 56(84) bytes of data. 64 bytes from iad30s21-in-f4.1e100.net (172.217.15.100): icmp_seq=1 ttl=48 time=1.18 ms 64 bytes from iad30s21-in-f4.1e100.net (172.217.15.100): icmp_seq=2 ttl=48 time=1.22 ms 64 bytes from iad30s21-in-f4.1e100.net (172.217.15.100): icmp_seq=3 ttl=48 time=1.23 ms 64 bytes from iad30s21-in-f4.1e100.net (172.217.15.100): icmp_seq=4 ttl=48 time=1.23 ms 64 bytes from iad30s21-in-f4.1e100.net (172.217.15.100): icmp_seq=5 ttl=48 time=1.23 ms 64 bytes from iad30s21-in-f4.1e100.net (172.217.15.100): icmp_seq=6 ttl=48 time=1.21 ms ^C --- www.google.com ping statistics --- 6 packets transmitted, 6 received, 0% packet loss, time 5007ms rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 1.183/1.220/1.237/0.018 ms

Network folks immediately turn to ping when there is a failure in communication. All it can really do is help you figure out which parts of the network are unreachable. ping does not know the difference between a computer that is turned off, a computer with a bad network card, a computer that is not running a ping server, or a computer behind a firewall or other device which filters (eats) ping packets (to prevent flooding attacks).

ifconfig and ip

ifconfig gets its name from “Interface config”. This command supports tons of options; you can use it to list all your network interfaces and their settings, assign/remove IP addresses to network interfaces, prevent interfaces from sending and receivings, messages, configure certain interfaces to use different media, and more. On Linux-flavored operating systems, ifconfig is obsolete; use ip instead.

Here are the network interfaces on my macOS machine as I am writing these notes:

$ ifconfig -a lo0: flags=8049<UP,LOOPBACK,RUNNING,MULTICAST> mtu 16384 options=1203<RXCSUM,TXCSUM,TXSTATUS,SW_TIMESTAMP> inet 127.0.0.1 netmask 0xff000000 inet6 ::1 prefixlen 128 inet6 fe80::1%lo0 prefixlen 64 scopeid 0x1 inet 127.94.0.3 netmask 0xff000000 inet 127.94.0.2 netmask 0xff000000 inet 127.94.0.1 netmask 0xff000000 nd6 options=201<PERFORMNUD,DAD> gif0: flags=8010<POINTOPOINT,MULTICAST> mtu 1280 stf0: flags=0<> mtu 1280 XHC20: flags=0<> mtu 0 en0: flags=8863<UP,BROADCAST,SMART,RUNNING,SIMPLEX,MULTICAST> mtu 1500 ether f4:5c:89:8f:48:4b inet6 fe80::803:3448:7939:ef29%en0 prefixlen 64 secured scopeid 0x5 inet 192.168.1.143 netmask 0xffffff00 broadcast 192.168.1.255 inet6 fd07:4a4:8f26::e7:5d1f:732e:db32 prefixlen 64 autoconf secured inet6 fd07:4a4:8f26::a52c:a032:efcc:b2c prefixlen 64 autoconf temporary inet6 2600:6c50:17f:ab91:146f:8df7:38c9:b51b prefixlen 64 autoconf secured inet6 2600:6c50:17f:ab91:b926:8b31:7b90:b2e prefixlen 64 autoconf temporary inet6 2600:6c50:17f:ab91:79ef:a4b1:2f92:1765 prefixlen 64 dynamic nd6 options=201<PERFORMNUD,DAD> media: autoselect status: active p2p0: flags=8843<UP,BROADCAST,RUNNING,SIMPLEX,MULTICAST> mtu 2304 ether 06:5c:89:8f:48:4b media: autoselect status: inactive awdl0: flags=8943<UP,BROADCAST,RUNNING,PROMISC,SIMPLEX,MULTICAST> mtu 1484 ether f6:7b:3f:0e:0b:85 inet6 fe80::f47b:3fff:fe0e:b85%awdl0 prefixlen 64 scopeid 0x7 nd6 options=201<PERFORMNUD,DAD> media: autoselect status: active en1: flags=8963<UP,BROADCAST,SMART,RUNNING,PROMISC,SIMPLEX,MULTICAST> mtu 1500 options=60<TSO4,TSO6> ether 6a:00:01:8b:25:40 media: autoselect <full-duplex> status: inactive en2: flags=8963<UP,BROADCAST,SMART,RUNNING,PROMISC,SIMPLEX,MULTICAST> mtu 1500 options=60<TSO4,TSO6> ether 6a:00:01:8b:25:41 media: autoselect <full-duplex> status: inactive bridge0: flags=8863<UP,BROADCAST,SMART,RUNNING,SIMPLEX,MULTICAST> mtu 1500 options=63<RXCSUM,TXCSUM,TSO4,TSO6> ether 6a:00:01:8b:25:40 Configuration: id 0:0:0:0:0:0 priority 0 hellotime 0 fwddelay 0 maxage 0 holdcnt 0 proto stp maxaddr 100 timeout 1200 root id 0:0:0:0:0:0 priority 0 ifcost 0 port 0 ipfilter disabled flags 0x2 member: en1 flags=3<LEARNING,DISCOVER> ifmaxaddr 0 port 8 priority 0 path cost 0 member: en2 flags=3<LEARNING,DISCOVER> ifmaxaddr 0 port 9 priority 0 path cost 0 nd6 options=201<PERFORMNUD,DAD> media: <unknown type> status: inactive utun0: flags=8051<UP,POINTOPOINT,RUNNING,MULTICAST> mtu 2000 inet6 fe80::f2a5:944f:38d3:f50c%utun0 prefixlen 64 scopeid 0xb nd6 options=201<PERFORMNUD,DAD>

And here is a run of the command on a Linux box I spun up on AWS EC2:

$ ifconfig -a

eth0: flags=4163<UP,BROADCAST,RUNNING,MULTICAST> mtu 9001

inet 172.31.47.36 netmask 255.255.240.0 broadcast 172.31.47.255

inet6 fe80::ce2:85ff:febc:f88e prefixlen 64 scopeid 0x20<link>

ether 0e:e2:85:bc:f8:8e txqueuelen 1000 (Ethernet)

RX packets 21067 bytes 28044612 (26.7 MiB)

RX errors 0 dropped 0 overruns 0 frame 0

TX packets 8559 bytes 606885 (592.6 KiB)

TX errors 0 dropped 0 overruns 0 carrier 0 collisions 0

lo: flags=73<UP,LOOPBACK,RUNNING> mtu 65536

inet 127.0.0.1 netmask 255.0.0.0

inet6 ::1 prefixlen 128 scopeid 0x10<host>

loop txqueuelen 1000 (Local Loopback)

RX packets 8 bytes 648 (648.0 B)

RX errors 0 dropped 0 overruns 0 frame 0

TX packets 8 bytes 648 (648.0 B)

TX errors 0 dropped 0 overruns 0 carrier 0 collisions 0

Better to use ip on Linux:

$ ip addr

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 ::1/128 scope host

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

2: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 9001 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether 0e:e2:85:bc:f8:8e brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 172.31.47.36/20 brd 172.31.47.255 scope global dynamic eth0

valid_lft 2902sec preferred_lft 2902sec

inet6 fe80::ce2:85ff:febc:f88e/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

traceroute

Displays information on the path (and the final host) together with trip times. For example:

Tracing route to staff.cs.utu.fi [130.232.75.8] over a maximum of 30 hops: 1 9 ms 56 ms 7 ms 10.234.64.1 2 9 ms 8 ms 9 ms cr01-gln1-ca.oc-nod.charterpipeline.net [24.205.0.97] 3 9 ms 10 ms 21 ms er01-mpk1-ca.oc-nod.charterpipeline.net [24.205.1.133] 4 9 ms 9 ms 9 ms bur-edge-02.inet.qwest.net [65.114.177.133] 5 13 ms 15 ms 10 ms bur-core-01.inet.qwest.net [205.171.13.17] 6 15 ms 24 ms 11 ms lax-core-01.inet.qwest.net [205.171.8.41] 7 10 ms 11 ms 12 ms lax-brdr-01.inet.qwest.net [205.171.19.38] 8 16 ms 12 ms 12 ms pos6-0.core1.LosAngeles1.Level3.net [209.0.227.41] 9 14 ms 12 ms 13 ms so-4-3-0.mp1.LosAngeles1.level3.net [209.247.9.141] 10 94 ms 71 ms 73 ms so-0-0-0.bbr2.Washington1.level3.net [64.159.1.158] 11 189 ms 144 ms 145 ms so-0-0-0.mp2.London2.Level3.net [212.187.128.133] 12 180 ms 181 ms 180 ms so-4-1-0.mpls1.Stockholm1.Level3.net [212.187.128.218] 13 181 ms 181 ms 181 ms 213.242.68.67 14 179 ms * 179 ms 213.242.69.18 15 184 ms 184 ms 183 ms fi-gw.nordu.net [193.10.68.42] 16 182 ms 182 ms 185 ms funet1-rtr.nordu.net [193.10.252.50] 17 185 ms 185 ms 188 ms abo0-p000-csc0.funet.fi [193.166.255.162] 18 184 ms 184 ms 184 ms abo3-g0000-abo0.funet.fi [193.166.187.22] 19 185 ms 186 ms 185 ms e2-funet.utu.fi [130.232.202.214] 20 186 ms 208 ms 187 ms kenny-ext.utu.fi [130.232.202.65] 21 189 ms 207 ms 187 ms kh2-sgext.rs.utu.fi [130.232.202.45] 22 210 ms 186 ms 188 ms multinet-rtr-alpine1.utu.fi [130.232.202.222] 23 186 ms 186 ms 187 ms staff.cs.utu.fi [130.232.75.8]

Some machines have traceroute disabled to prevent flooding attacks.

See traceroute.org for a list of links to sites that have made traceroute services from their hosts available to you on the web.

The description, number of options, and the large amounts of information output by this command can be found in the man page, do check it out.

dig

The domain information groper. Performs name to address lookups by querying DNS servers. Similar commands include nslookup and host.

From the man page: dig (domain information groper) is a flexible tool for interrogating DNS name servers. It performs DNS lookups and displays the answers that are returned from the name server(s) that were queried. Most DNS administrators use dig to troubleshoot DNS problems because of its flexibility, ease of use and clarity of output. Other lookup tools tend to have less functionality than dig.

Here’s a run:

$ dig zoodiker.com any ; <<>> DiG 9.10.6 <<>> zoodiker.com any ;; global options: +cmd ;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 28185 ;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 9, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 9 ;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION: ; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 512 ;; QUESTION SECTION: ;zoodiker.com. IN ANY ;; ANSWER SECTION: zoodiker.com. 7200 IN NS ns-1195.awsdns-21.org. zoodiker.com. 7200 IN NS ns-1617.awsdns-10.co.uk. zoodiker.com. 7200 IN NS ns-474.awsdns-59.com. zoodiker.com. 7200 IN NS ns-535.awsdns-02.net. zoodiker.com. 900 IN SOA ns-1195.awsdns-21.org. awsdns-hostmaster.amazon.com. 1 7200 900 1209600 86400 zoodiker.com. 60 IN A 99.84.194.100 zoodiker.com. 60 IN A 99.84.194.28 zoodiker.com. 60 IN A 99.84.194.30 zoodiker.com. 60 IN A 99.84.194.5 ;; ADDITIONAL SECTION: ns-1195.awsdns-21.org. 7200 IN A 205.251.196.171 ns-1195.awsdns-21.org. 7200 IN AAAA 2600:9000:5304:ab00::1 ns-1617.awsdns-10.co.uk. 7200 IN A 205.251.198.81 ns-1617.awsdns-10.co.uk. 7200 IN AAAA 2600:9000:5306:5100::1 ns-474.awsdns-59.com. 7200 IN A 205.251.193.218 ns-474.awsdns-59.com. 7200 IN AAAA 2600:9000:5301:da00::1 ns-535.awsdns-02.net. 7200 IN A 205.251.194.23 ns-535.awsdns-02.net. 7200 IN AAAA 2600:9000:5302:1700::1 ;; Query time: 38 msec ;; SERVER: 2607:f428:ffff:ffff::1#53(2607:f428:ffff:ffff::1) ;; WHEN: Sun Jan 27 12:22:56 PST 2019 ;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 479

netstat

Gives information on your machine's Internet connection and activity. Displays network connections, routing tables, interface statistics, masquerade connections, netlink messages, and multicast messages.

The -r shows routing tables. On my Mac:

$ netstat -r Routing tables Internet: Destination Gateway Flags Refs Use Netif Expire default 192.168.1.1 UGSc 140 0 en0 127 localhost UCS 0 0 lo0 localhost localhost UH 13 1608781 lo0 client.openvpn.net client.openvpn.net UH 0 8812 lo0 openvpn-client.vpn openvpn-client.vpn UH 0 8812 lo0 openvpn-client.vpn openvpn-client.vpn UH 0 8812 lo0 169.254 link#5 UCS 0 0 en0 192.168.1 link#5 UCS 3 0 en0 192.168.1.1/32 link#5 UCS 1 0 en0 192.168.1.1 c0:56:27:19:7b:e8 UHLWIir 65 85 en0 995 192.168.1.109 b4:6b:fc:da:94:72 UHLWIi 1 0 en0 438 192.168.1.127 e0:ac:cb:65:bd:5e UHLWI 0 0 en0 192.168.1.133 a4:77:33:9c:6f:ae UHLWIi 1 7082 en0 1170 192.168.1.143/32 link#5 UCS 1 0 en0 192.168.1.143 f4:5c:89:8f:48:4b UHLWI 0 2 lo0 224.0.0/4 link#5 UmCS 2 0 en0 224.0.0.251 1:0:5e:0:0:fb UHmLWI 0 0 en0 239.255.255.250 1:0:5e:7f:ff:fa UHmLWI 0 588 en0 255.255.255.255/32 link#5 UCS 0 0 en0

The -an options are often used with grep to see what’s going on at a cerain port:

$ netstat -an | grep 3000 tcp4 0 0 127.0.0.1.3000 127.0.0.1.62131 ESTABLISHED tcp4 0 0 127.0.0.1.62131 127.0.0.1.3000 ESTABLISHED tcp4 0 0 *.3000 *.* LISTEN

There are a zillion more options for this command. Defintely checkout the man pages.

lsof

Lists open files. From the man page: Lsof ... lists on its standard output file information about files opened by processes for [various] following UNIX dialects [macOS, FreeBSD, Linex, Solaris]. If you grep for the string LISTEN you can see which ports are open for receiving data.

Not much going on on this EC2 box I spun up:

$ sudo lsof -i -P -n | grep LISTEN rpcbind 2675 rpc 8u IPv4 17053 0t0 TCP *:111 (LISTEN) rpcbind 2675 rpc 11u IPv6 17056 0t0 TCP *:111 (LISTEN) master 3148 root 13u IPv4 18899 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:25 (LISTEN) sshd 3286 root 3u IPv4 20490 0t0 TCP *:22 (LISTEN) sshd 3286 root 4u IPv6 20499 0t0 TCP *:22 (LISTEN)

But checkout what I’ve got running on my laptop:

$ sudo lsof -i -P -n | grep LISTEN Password: openvpn-s 74 root 3u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1aff3453 0t0 TCP 127.94.0.3:946 (LISTEN) openvpn-s 74 root 4u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1aff0ed3 0t0 TCP 127.94.0.2:946 (LISTEN) openvpn-s 74 root 7u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1aff2193 0t0 TCP 127.94.0.1:946 (LISTEN) nfsd 235 root 7u IPv4 0x50b4f27e16044af3 0t0 TCP *:1023 (LISTEN) nfsd 235 root 8u IPv6 0x50b4f27e160486ab 0t0 TCP *:1022 (LISTEN) nfsd 235 root 9u IPv4 0x50b4f27e16044193 0t0 TCP *:2049 (LISTEN) nfsd 235 root 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e16048c6b 0t0 TCP *:2049 (LISTEN) cupsd 241 root 6u IPv6 0x50b4f27e219d3dab 0t0 TCP [::1]:631 (LISTEN) cupsd 241 root 7u IPv4 0x50b4f27e209f8833 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:631 (LISTEN) rpc.statd 246 root 7u IPv4 0x50b4f27e16042ed3 0t0 TCP *:1021 (LISTEN) rpc.statd 246 root 8u IPv6 0x50b4f27e16049dab 0t0 TCP *:1019 (LISTEN) rpcbind 247 daemon 4u IPv4 0x50b4f27e16043833 0t0 TCP *:111 (LISTEN) rpcbind 247 daemon 6u IPv6 0x50b4f27e160497eb 0t0 TCP *:111 (LISTEN) rpc.lockd 249 root 6u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1afbd453 0t0 TCP *:1017 (LISTEN) rpc.lockd 249 root 7u IPv6 0x50b4f27e160480eb 0t0 TCP *:1012 (LISTEN) rapportd 374 ray 3u IPv4 0x50b4f27e4481e193 0t0 TCP *:57043 (LISTEN) rapportd 374 ray 4u IPv6 0x50b4f27e1b0004ab 0t0 TCP *:57043 (LISTEN) rpc.rquot 434 root 6u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1b06e833 0t0 TCP *:1004 (LISTEN) rpc.rquot 434 root 7u IPv6 0x50b4f27e1affd0eb 0t0 TCP *:1000 (LISTEN) ZoomOpene 456 ray 3u IPv4 0x50b4f27e41d15ed3 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:19421 (LISTEN) redis-ser 469 ray 6u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1c118af3 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:6379 (LISTEN) postgres 477 ray 5u IPv6 0x50b4f27e1b071b2b 0t0 TCP [::1]:5432 (LISTEN) postgres 477 ray 6u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1c117833 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:5432 (LISTEN) epmd 680 ray 3u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1b06f193 0t0 TCP *:4369 (LISTEN) epmd 680 ray 4u IPv6 0x50b4f27e1b072c6b 0t0 TCP *:4369 (LISTEN) mysqld 695 ray 20u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1fe3aed3 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:3306 (LISTEN) beam.smp 728 ray 80u IPv4 0x50b4f27e200bb193 0t0 TCP *:25672 (LISTEN) beam.smp 728 ray 92u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1eb0b833 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:5672 (LISTEN) beam.smp 728 ray 93u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0592b 0t0 TCP *:61613 (LISTEN) beam.smp 728 ray 94u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d07c6b 0t0 TCP *:1883 (LISTEN) beam.smp 728 ray 95u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1e40eed3 0t0 TCP *:15672 (LISTEN) node 22652 ray 26u IPv4 0x50b4f27e3fea5193 0t0 TCP *:3000 (LISTEN) Discord 27367 ray 49u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1eb0c193 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:6463 (LISTEN) Box\x20Lo 37877 ray 4u IPv4 0x50b4f27e1d290af3 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:17223 (LISTEN) Box\x20Lo 37877 ray 5u IPv6 0x50b4f27e219d37eb 0t0 TCP [::1]:17223 (LISTEN) ssh 45883 ray 8u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d04dab 0t0 TCP [::1]:33062 (LISTEN) ssh 45883 ray 9u IPv4 0x50b4f27e21273833 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:33062 (LISTEN) Code\x20H 69299 ray 34u IPv4 0x50b4f27e41432453 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:30237 (LISTEN) Code\x20H 69300 ray 34u IPv4 0x50b4f27e4401ced3 0t0 TCP 127.0.0.1:28484 (LISTEN) mysqld 77599 ray 10u IPv4 0x50b4f27e43e73833 0t0 TCP *:3306 (LISTEN) httpd 77620 root 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77628 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77629 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77630 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77631 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77632 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77633 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77661 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77670 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77671 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77672 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN) httpd 77673 ray 10u IPv6 0x50b4f27e23d0992b 0t0 TCP *:80 (LISTEN)

So I got a webserver running at port 80, a Redis server running at 6379, Postgres at 5432, MySQL at 3306. All those ports are pretty standard. My Discord server is running at 6463. The node process at 3000 is because I‘m writing a React app and testing it locally.

Do some explorations with traceroute and netstat.

Graphical Tools

The command line is great, but colorful pictures are great too. Let’s browse:

- Wireshark

- The Browser’s Devtools Network Tab

in class.

Summary

We’ve covered:

- A very brief internet history

- Internet Architecture

- The Edge and the Core

- What and RFC is, what a protocol is

- Some command line network tools

- Some graphical network tools