Subroutines

What is a Subroutine?

Rather than settle for a simple definition, we need to learn a number of related terms.

- A subroutine (also called a subprogram) is an abstraction of a process that is called.

- The caller passes arguments to the subroutine which accepts them as parameters.

- While the caller waits, the subroutine executes (or evaluates) its body, which may cause side effects to the global system state, and optionally returns results to the caller.

- A function returns a value or values and is called from within an expression.

- A procedure returns no values and is called in a statement, not an expression. But some languages have no statements (only expressions). The languages use some mechanism like "void context" or employ a special return value like

nilor()to make functions look like procedures. - A method is a subroutine defined on an object in an object oriented context.

Subroutines vs. CoroutinesBoth subroutines and coroutines are named blocks of code with parameters. And in many languages they are defined quite similarly.

But there is a huge characteristic difference: Every time a subroutine is called it starts at the beginning and runs until it returns. A coroutine starts at the beginning the first time it is called, but it can yield, rather than return, so the next time it is called, it picks up from the point it last yielded.

Though these notes focus on subroutines, much of what is said applies to both kinds of routines.

Subroutine Signatures

What is a Signature?

A subroutine's signature specifies the number, order, names, modes and types of its parameters and return values. Roughly speaking, something like this:

// Declaration specifies the subroutine name and its signature subroutine f(p1: m1 T1, p2: m2 T2, ... pn: mn Tn) returns T0; // Here is an example call T0 x = f(e1, e2, ... ek);

Note that:

- In many languages, the parameters don't have types, nor does the return value.

- The set of modes differ between languages, but are usually things like in, out, in out, alias, reference, value. (More on this later when we look at argument passing.) It’s actually pretty typical for a language to just have one mode—value—which is never specified explicitly.

But also keep in mind this is a ridiculous simplification anyway. What about default parameter values? What about rest parameters? What about pattern matching?

Signature Matching

The point of signatures is to distinguish legal calls from illegal calls. Languages differ wildly in how they define whether or not a call matches a signature.

- Do the parameter names matter?

- Does the order matter?

- Do the types matter? Does it even make sense to put type restrictions on parameters?

- Does the number of arguments in the call matter? What if we pass too few? Too many?

- How do the modes affect what can and cannot be passed?

- Do the return types matter?

- Can the subroutine be called as part of a statement or must it be called in an expression?

- Can the subroutine be called as part of an expression or must it be called in a statement?

- Hey I want patterns for my parameters, rather than specifying them directly!

Very "static" languages have a rule like:

k=n and the type of each ei must be compatible with the corresponding Ti

but many languages have many different rules.

Parameter Association

How do we know which argument goes with which parameter? Many answers to this question! Let’s start with languages without patterns.

Positional and Named Association

Virtually every language supports positional association: the first argument goes with the first parameter; the second argument goes with the second parameter, and so on. Ada allows both positional and named association. The order of the named arguments don’t matter. You can mix then two styles, but the positional ones must go first:

procedure P(X: Integer; Y: Float; C: Duration; B: Boolean); P(1, 9.3, 30.0, True); P(X => 4, B => False, C => 4.0, Y => 35.66); P(B => True, C => 12.0, Y => -11.4 * Z, X => 1); P(C => 12.0, Y => -11.4, B => Found or not Odd(Q), X => 1); P(8, 4.2, B => True, C => Stop_Time - End_Time); procedure Push(On_The_Stack: Stack, The_Value: Character); Push(On_The_Stack => S, The_Value => '$'); Push(The_Value => '^', On_The_Stack => T);

Python is the same. It calls the named ones keyword arguments:

def draw_line(from, to, red, green, blue, width, style):

...

draw_line([3, 5], [3, 9], green=0.4, red=0.1, style="dashed", width=3, blue=1.0)

draw_line(red=0.0, green=0.0, blue=0.3, style="solid", to=[1,1], from=[9,8], width=1)

In Ruby, you mark the parameters that must be named with a colon:

def f(x, y:, z:) [x, y, z] end puts(f(13, z: 5, y: 2))

You can even fake named association by passing in dictonary literals. Try it.

Overloading

With overloaded subroutines the compiler has to figure out which subroutine is being called; this is called overload resolution.

How to deal with ambiguity? Is the return type considered? Are the modes? How about the number of arguments, when variadic subroutines are in the mix? Should we search in outer scopes, even when subroutines of the same name are "closer" to the call? Should ambiguities be detected at the point of call, or at the point of declaration?

Default Parameters

Super common:

// JavaScript

function f(int x, int y = 1, int z = 0) {

return x * y + z;

}

// f(4, 3, 9) returns 21

// f(4, 3) returns 12

// f(4) returns 4

-- Ada function F(X: Integer; Y: Integer := 1; Z: Integer := 0) return Integer is begin return X * Y + Z; end F; -- F(4, 3, 9) returns 21 -- F(4, 3) returns 12 -- F(4) returns 4

// C++

int f(int x, int y = 1, int z = 0) {

return x * y + z;

}

// f(4, 3, 9) returns 21

// f(4, 3) returns 12

// f(4) returns 4

; Common Lisp (defun f (x &optional (y 1) (z 0)) (+ (* x y) z)) ; (f 4 3 9) returns 21 ; (f 4 3) returns 12 ; (f 4) returns 4

You fake them in Perl because all the arguments are passed in one big list:

sub f {

die "At least one argument required" if not @_;

my $x = shift;

my $y = @_ ? shift : 1;

my $z = @_ ? shift : 0;

return $x * $y + $z;

}

Some languages have de facto defaults -- if you don't call the subroutine with enough arguments, the "missing" parameters automatically get some kind of undefined or null value.

Variadic Subroutines

A variadic subroutine can accept an arbitrary number of parameters.

In Lisp, you make a function variadic by marking the last parameter with &rest.

(defun f (x &rest y) (* x (apply #'+ y))) ; (f 2) means x=2 and y=() ; (f 3 5) means x=3 and y=(5) ; (f 2 8 7 5 3 4) means x=2 and y=(8 7 5 3 4)

In Perl, all subroutines are variadic, since all arguments are collected into the array @_.

sub f {

my $x = shift;

my $result = 0;

$result += $_ for (@_);

return $x * $result;

}

f 2 == 0 or die;

f 3, 5 == 15 or die;

f 2, 8, 7, 5, 3, 4 == 54 or die;

In Java, you can mark the last parameter of a method with "..." to mean that it is really an array and the caller can pass in a variable number of arguments without the clunkiness of putting them in an array.

public static int f(int x, int... y) {

int result = 0;

for (int a : y) result += a;

return x * result;

}

// f(2) means x=2 and y=new int[]{} and returns 0

// f(3,5) means x=3 and y=new int[]{5} and returns 15

// f(2,8,7,5,3,4) means x=2 and y=new int[]{8,7,5,3,4} and returns 54

Same in JavaScript:

function f(x, ...y) {

let result = 0

for (const a of y) result += a

return x * result;

}

// f(2) means x=2 and y=[] and returns 0

// f(3,5) means x=3 and y=[5] and returns 15

// f(2,8,7,5,3,4) means x=2 and y=[8,7,5,3,4] and returns 54

Python is similar. A parameter prefixed with "*" collects the extra parameters into a list. With "**" the extras are collected into a dictionary. Here is the example from the Python tutorial:

def cheeseshop(kind, *arguments, **keywords):

print "-- Do you have any", kind, "?"

print "-- I'm sorry, we're all out of", kind

for arg in arguments:

print arg

print "-" * 40

keys = sorted(keywords.keys())

for kw in keys:

print kw, ":", keywords[kw]

cheeseshop("Limburger", "It's very runny, sir.",

"It's really very, VERY runny, sir.",

shopkeeper='Michael Palin',

client="John Cleese",

sketch="Cheese Shop Sketch")

In C, you need the stdarg.h library module and a lot of code.

#include <assert.h>

#include <stdarg.h>

/*

* f(k, x, y1, y2, y3, ..., yk) returns the value of

* x * sum(y1 ... yk). Note that because this is C,

* you have to pass in the argument count!

*/

int f(int k, int x, ...) {

int result = 0;

va_list ap;

va_start(ap, x); /* x is the param just before the extras */

while (k--) { /* simple count down */

int y = va_arg(ap, int);

result += y; /* sum up the extras */

}

va_end(ap);

return x * result;

}

int main() {

assert( f(2, 2, 5, 9) == 28 );

assert( f(3, 2, 1, 6, 2) == 18 );

assert( f(0, 2) == 0 );

assert( f(1, 2, 50) == 100 );

assert( f(9, 4, 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 5) == 68 );

}

Patterns

In JavaScript, function declarations don’t necessarily have parameters, they have patterns. JavaScript has both array patterns and object patterns:

function f([a, b], {x: y, c: {d: z}}) {

return [a, b, y, z];

}

f([3, 5, 8, 13], {c: {d: 1, e: 7}, p: 10, x: 21}); // [3, 5, 21, 1]

The ML languages do pattern matching pretty much just on constructors:

third :: (a,b,c) -> c third (_, _, z) = z firstTwoEqual :: (Eq a) => [a] -> Bool firstTwoEqual [] = False firstTwoEqual [x] = False firstTwoEqual (x:y:_) = x == y isSeven :: (Integral a) => a -> Bool isSeven 7 = True isSeven _ = False

Function Returns

How hard could it be to just return something? Again, there are so many questions:

- How many return values can a subroutine have (0, 1, many)?

- Perl — any number

- In the ML family — exactly one (to get 0, return unit; to get more, return a tuple)

- Most other languages — zero or one

- What kinds of objects can and cannot be returned from a subroutine?

- Algol 60 and Fortran — scalar only

- Pascal — scalar or pointer only

- Ada 83, C — anything but an actual function, though pointers to functions okay

- Ada 95, Modula-3 — can return closures too

- Most dynamic languages — can return anything

- How is (are) the return value(s) specified?

- Pascal, Fortran — special variable with the name of the subroutine gets assigned to.

- Eiffel has a variable called "Result"

- In SR, you "declare" the result variable in the subroutine signature

- Most other languages — an explicit return statement

- Could also be the last expression in the body (e.g. Perl, Ruby, many others)

Go is really flexible here:

func swap(x, y string) (string, string) {

return y, x

}

// Wow you can name the return value(s)

func divmod(x, y int) (quo, rem int) {

quo = x / y

rem = x % y

return

}

Argument Passing

Passing arguments to parameters looks so simple, right?. It’s just:

function f(x) {

...

}

f(y);

And yet, there are so many questions. The questions fall in two broad categories:

- [Semantic] Can x be written to in the body of f, and if so, will the change be made in y, and if y does change, does the change happen right away or only after f returns?

- [Pragmatic] What exactly happens at the call? Is a copy of y made and passed to x? Are x and y to be aliases? Is the "address" of y passed? Is a block of code to evaluate y passed?

Common mechanisms

People have identified a bunch of mechanisms over time:

- in (const) — callee can't write to the parameter.

- out — callee can't read the parameter; it just sends the value out at the end.

- in out — Callee can read and write parameter; changes to parameter are reflected in the argument (but we don't know if the argument sees the update during or only after the execution of the callee).

- by value — Argument value is copied to the parameter; changes to parameter are not reflected in argument.

- by value/result — Argument value copied in; parameter value copied out at end of callee.

- aliasing (sharing) — argument and parameter are one. Changes to parameter immediately are seen in the argument, because, as was just mentioned, the argument and parameter are one.

- by reference — An implementation of aliasing through passing the address of the argument.

- by name — Parameter is more or less a macro, taking on the source code text of the argument.

Michael L. Scott made a nice summary:

| Implementation | Allowable operations on parameter |

Can argument change? | Aliasing? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in | any | R | No | Maybe |

| out | any | W | Yes | Maybe |

| in out | any | RW | Yes | Maybe |

| value | value | RW | No | No |

| value-result | value | RW | Yes | No |

| sharing | any | RW | Yes | Yes |

| reference | address | RW | Yes | Yes |

| name | closure | RW | Yes | Yes |

Generic Subroutines

In statically typed languages, how can we say that a parameter can be passed arguments from different types?

In C++ and Ada the compiler generates code for every instance of a "generic" subroutine. In C++ each actual subroutine is implicitly generated when needed:

// ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

// mintemplate.cpp

//

// This program illustrates the declaration of a template function and how

// it can be called with many different types, including user-defined ones.

// ---------------------------------------------------------------------------

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

template <class T>

T minimum(T x, T y) {

return x < y ? x : y;

}

class A {

int x;

int y;

public:

A(int x, int y): x(x), y(y) {}

bool operator<(A other) {return x + y < other.x + other.y;}

friend ostream& operator<<(ostream& s, A a) {

return s << "(" << a.x << "," << a.y << ")";

}

};

// Show it off

int main() {

cout << minimum(4, 5) << "\n";

cout << minimum(3.3, 4.1) << "\n";

cout << minimum("dog", "bat") << "\n";

cout << minimum(A(1,3), A(6,0)) << "\n";

cout << minimum(A(5,5), A(6,0)) << "\n";

cout << minimum(A(9,1), A(2,1)) << "\n";

cout << minimum(A(2,3), A(-6,0)) << "\n";

return 0;

}

But in Ada you have to implicitly instantiate them:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-- generic_min_demo.adb

--

-- This program illustrates the declaration of a generic function and how

--/ it can be called with many different types, including user-defined ones.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

with Ada.Text_IO, Ada.Integer_Text_IO, Ada.Float_Text_IO;

use Ada.Text_IO, Ada.Integer_Text_IO, Ada.Float_Text_IO;

procedure Generic_Min_Demo is

-- Define a generic Minimum function callable on any type.

-- The second parameter is a default parameter. Cool, eh?

generic

type T is limited private;

with function "<"(X: T; Y: T) return Boolean is <>;

function Minimum(X: T; Y: T) return T;

function Minimum(X: T; Y: T) return T is

begin

if X < Y then

return X;

else

return Y;

end if;

end Minimum;

-- Make a user defined type called A, with "<" and Put operations.

type A is record

X: Integer;

Y: Integer;

end record;

function "<"(X: A; Y: A) return boolean is

begin

return X.X + X.Y < Y.X + Y.Y;

end "<";

procedure Put (X: A) is

begin

Put ("(");

Put (X.X, 0);

Put (",");

Put (X.Y, 0);

Put (")");

end Put;

-- Instantiate a few

function Min_Integer is new Minimum(Integer);

function Min_Float is new Minimum(Float);

function Min_A is new Minimum(A);

-- Show off the calls

begin

Put(Min_Integer(4, 5), 0); New_Line;

Put(Min_Float(3.3, 4.1), 0); New_Line;

Put (Min_A(A'(1,3), A'(6,0))); New_Line;

Put (Min_A(A'(5,5), A'(6,0))); New_Line;

Put (Min_A(A'(9,1), A'(2,1))); New_Line;

Put (Min_A(A'(2,3), A'(-6,0))); New_Line;

end Generic_Min_Demo;

Here's an example of a Java generic method:

public static <T, S extends T> boolean in(S x, T[] a) {

for (T y : a) {

if (y.equals(x)) return true;

}

return false;

}

Subroutines as Values

Many times, especially in event-driven systems such as GUIs, event-based servers, or asynchronous message handlers, we need to call subroutines indirectly. The actual subroutine to call is not known until run-time, so we need subroutines to be values (or at least the notion of a reference to a subroutine).In some languages, a subroutine s may be "just another object," like an integer, string or list. If so, we can ask these questions:

- Does s have a type and if so, what is it, and what are the type equivalence and compatibility rules?

- Can s be assigned to a variable?

- Can s be passed as an argument to a subroutine?

- Can s be returned from a subroutine?

- Can we generate a new (unnamed) subroutine on the fly, at run time?

In ML, Lisp, Scheme, Haskell, Clojure and other "functional" languages, then answer to all 5 questions is definitely yes.

Other languages answer many of these questions no, but others might say the answer is technically no but allow references to subroutines everywhere.

Closures

If your language lets you (1) store subroutines as values, and (2) nest subroutines, then you can make closures. A closure is a subroutine that refers to variables defined in an enclosing scope.

function counterFrom(start) {

let number = start;

return function(increment) {

number += increment;

return number;

}

}

const c1 = counterFrom(20);

const c2 = counterFrom(100);

alert(c1(2));

alert(c1(5));

alert(c2(3));

alert(c1(4));

alert(c2(1));

They are interesting when the enclosing scope itself is a function, because when the enclosing function goes out of scope, its local variables must be retained because instances of the inner function might still need them! This is both powerful, but you have to be careful not to fill up memory since a lot of stuff becomes ineligible for garbage collection.

Study:

- Wikipedia article on closures

- Martin Fowler's bliki page on closures

- Closures in Perl

- JavaScript closures (Great, easy introduction)

- JavaScript closures (with a lot of technical detail)

- Closures in Python

Subroutines as Arguments

At first glance, passing subroutines as arguments doesn't appear to raise any scoping problems:

fun twice f x = f(f(x)); fun square x = x * x; fun addSix x = x + 6; twice square 5; twice addSix 8; twice (fn x => x / 2.0) 1.0; twice (fn x => x ^ "ee");

typedef int fun(int);

int square(int x) {return x * x;}

int addSix(int x) {return x + 6;}

int twice(fun f, int x) {return f(f(x));}

int main() {

printf("%d\n", twice(square, 5));

printf("%d\n", twice(addSix, 8));

return 0;

}

sub twice {

my ($f, $x) = @_;

return &$f(&$f(x)); # or $f->$f->(x)

}

sub square {$_[0] * $_[0];}

sub addSix {$_[0] + 6;}

print twice(\&square, 5), "\n";

print twice(\&addSix, 8), "\n";

function twice (f, x) {return f(f(x));}

function square(x) {return x * x;}

function addSix(x) {return x + 6;}

twice(square, 5);

twice(addSix, 8);

with Ada.Text_IO, Ada.Integer_Text_IO;

use Ada.Text_IO, Ada.Integer_Text_IO;

procedure Twice_Demo is

type Fun is access function(X: Integer) return Integer;

function Twice(F: Fun; X: Integer) return Integer is

begin

return F.all(F.all(X));

end Twice;

function Square(X: Integer) return Integer is

begin

return X * X;

end Square;

function Add_Six(X: Integer) return Integer is

begin

return X + 6;

end Add_Six;

begin

Put(Twice(Square'Access, 5));

New_Line;

Put(Twice(Add_Six'Access, 8));

New_Line;

end Twice_Demo;

However, what happens when you pass a subroutine which references non-local variables? Do we use the referencing environment that is in place when the subroutine is passed? Or the one in place when the (passed) subroutine is eventually called?

Deep and Shallow Binding

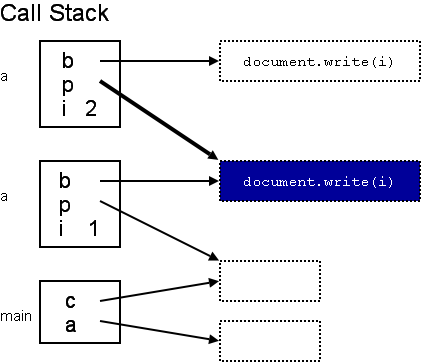

Consider the following code (from Scott's book, here ported to JavaScript):

function a(i, p) {

function b() {document.write(i);}

if (i > 1) p(); else a(2, b);

}

function c() {}

a(1, c);

Let's trace the execution....

The function in blue is defined in the context of the first activation of a in which i is 1, but is called from a context in which i is 2. Some languages will be defined to use one or the other. We say the language uses:

- Deep Binding — if it uses bindings at time of definition

- Shallow Binding — if it uses bindings at time of call

Try the same example in different languages...

# Perl

sub a {

my ($i, $p) = @_;

sub b {print "$i\n";}

if ($i > 1) {

&$p();

} else {

&a(2, \&b);

}

}

sub c {}

&a(1, \&c);

(* Standard ML *)

fun a(i: int, p: unit->unit) =

let

fun b() = print(if i=1 then "Deep" else "Shallow")

in

if i > 1 then p() else a(2, b)

end;

fun c() = ();

a(1,c);

Recall Practice

Here are some questions useful for your spaced repetition learning. Many of the answers are not found on this page. Some will have popped up in lecture. Others will require you to do your own research.

- What is the difference between a subroutine and a coroutine?

- What is the difference between a parameter and an argument?

- What are the two main ways of associating an argument with a parameter?

- What is a default parameter?

- What does it mean for a subroutine to be variadic?

- What is a rest parameter?

- JavaScript and Erlang functions are defined with something more sophisticated that simple parameters. What is this powerful concept and how is it more sophisticated?

- Explain the three semantic mechanisms for argument passing (in, out, and in-out).

- Explain the following five pragmatic mechanisms for argument passing (value, value-result, reference, name, pure-aliasing).

- Why have some languages created “generic” subroutines? Isn’t this whole concept unnecessary given the more general concept of parameterized and dependent types? Why or why not?

- What is a closure?

Summary

We’ve covered:

- Definitions of “subroutine” and related terms

- Signatures

- Parameter association

- Positional vs, named association

- Overloading

- Default parameters

- Variadic routines

- Patterns for parameter matching

- Argument passing

- Function returns

- Generics

- Subroutine values

- Closures

- Subroutines as arguments (higher-order functions)